The dispute over Astoria and Long Island City’s border, settled

Where is the border between the two neighborhoods? And why does it matter so much?

As a child, Nachayka Vanterpool and her family watched the Fourth of July fireworks by the East River every year. She grew up in Ravenswood, a public housing project in Long Island City (LIC), Queens. They would walk 20 minutes to an industrial no-man’s-land by the waterfront, where they sat on the ground and watched fireworks. When the area’s first high rise, Citylights tower, shot up in 1996, Vanterpool remembered looking up at the building, wondering what it was like to watch the fireworks from there instead. Today, the area is unrecognizable. A 2017 New York Magazine article put it aptly: “Queens now has a skyline, and a restless one.” Long Island City has changed, and it’s dragging the neighborhood’s boundaries with it.

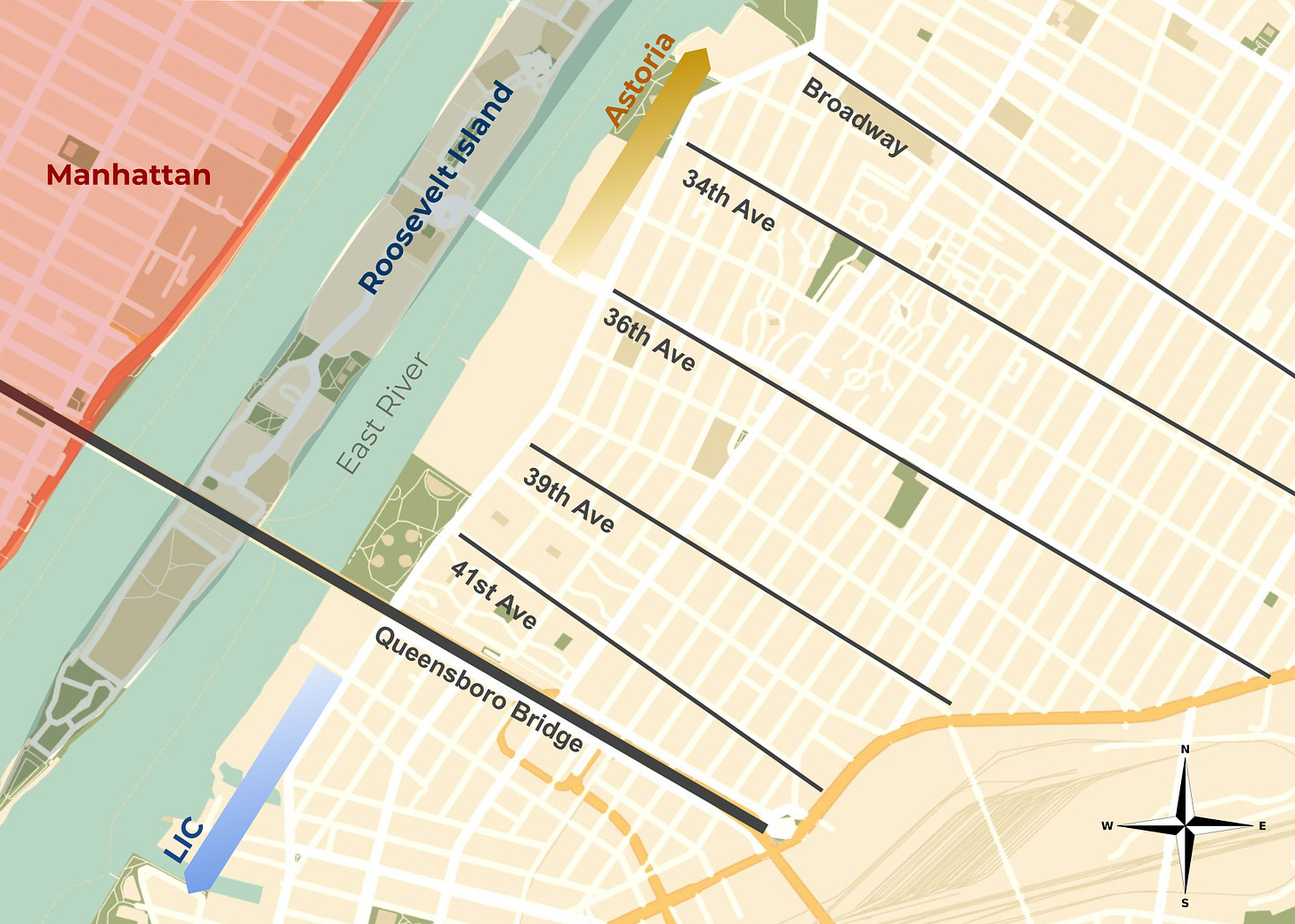

No one can agree on where Long Island City ends and Astoria starts. When we put out an online survey in June 2023, nearly 800 people responded within three days, and the comment sections below our Facebook and Reddit posts became battle grounds for intense debates among residents of the two neighborhoods of Western Queens.1

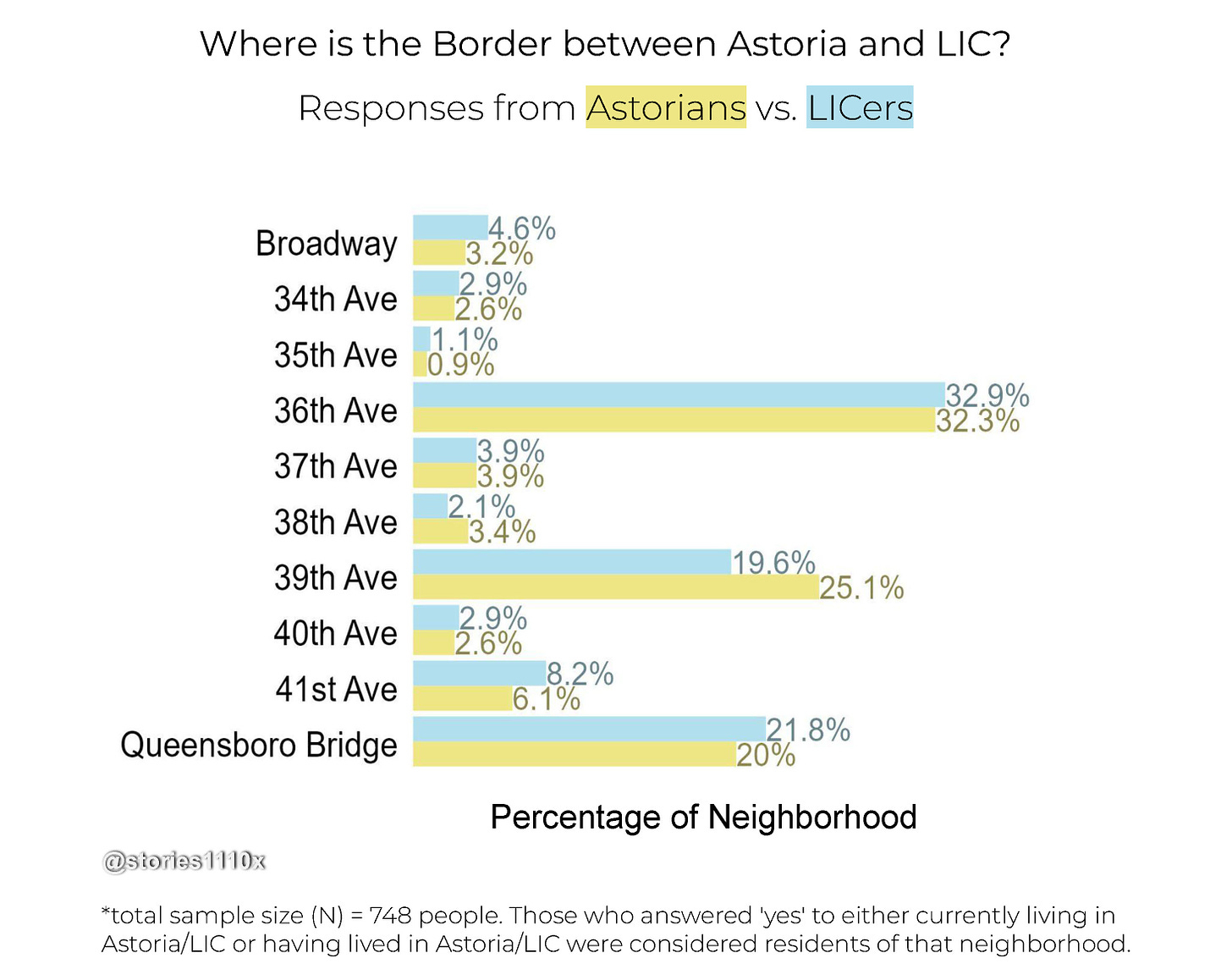

Our survey results show that people are very divided over this seemingly simple question: Where is the border?

The most popular answer — 36th Ave — only received a third of total votes, and that’s as much consensus as we can get for this question. 36th Ave is where Google Maps marks LIC’s cut-off and where Astoria’s landmark Kaufman Studio begins.

Queensboro Bridge was the second most popular response. The bridge is where the high rises end and the cityscape blends into shorter homes. Third place was 39th Ave, the awkward middle ground cutting across the Dutch Kills neighborhood, which is straddled between definitely-LIC and definitely-Astoria areas. (More on Dutch Kills later.)

More importantly, self-identified LICers are more likely to think that the border is at the Queensboro Bridge. Self-identified Astorians, on the other hand, are more likely to think the border is 39th Ave. To understand why that’s the case, and why people get so worked up over this question, we need a little history.

A brief history of LIC

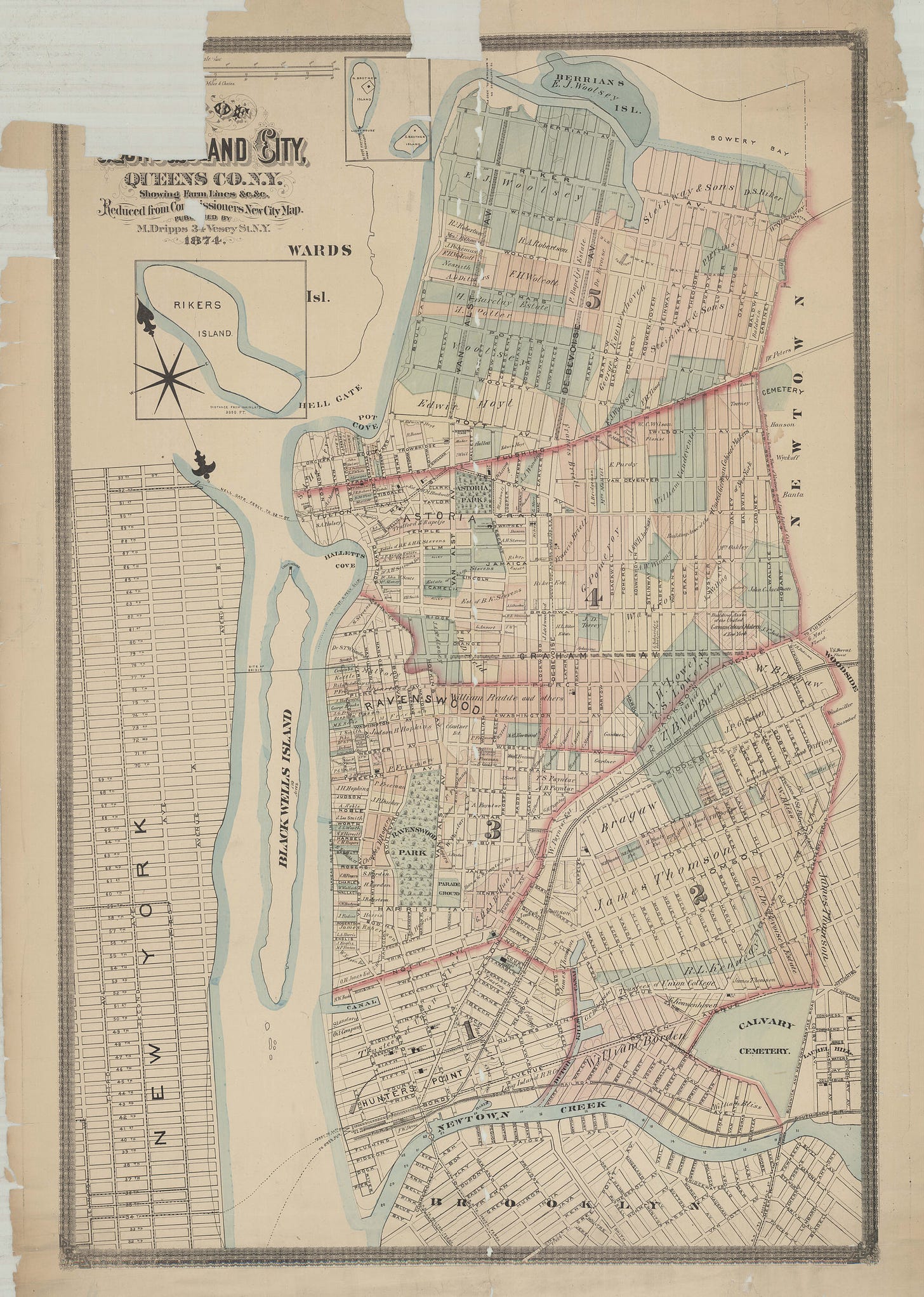

Long Island City used to be a city of its own. In 1870, multiple villages consolidated to form Long Island City, and the village names should still ring a bell for residents today: Hunters Point, Dutch Kills, Astoria, and Ravenswood. The entire Western Queens area was considered Long Island City. In 1898, Queens was annexed by New York City, putting an end to LIC’s brief glory as an independent metro.

In the early 1900s, the extensive growth of infrastructure sliced up Western Queens into the geography we’re familiar with today — the Queensboro Bridge was completed in 1909, Sunnyside Yards a year after the bridge, and the subway came to Queens in 1915. This isolated the southwestern corner of Queens from the rest of the city.

In an attempt to explain why LIC had remained industrial and deserted for so long despite its proximity to Manhattan, New York Magazine published in 2017:

“[LIC]’s also — subways aside — isolated from the rest of the city by the infrastructure… People don’t really just wander through, get inspired by a charming, underutilized space, and decide to open a restaurant.”

In 1980, the New York Times ran an article titled “The Next Neighborhood: Long Island City,” in which it said: “What exactly is going on in Long Island City? Most New Yorkers don’t even know where it is. And those who do, know it best for the wrong things.” The writer proceeded to describe a subway slasher, a factory explosion, and the neighborhood’s wide expanse of delivery trucks.

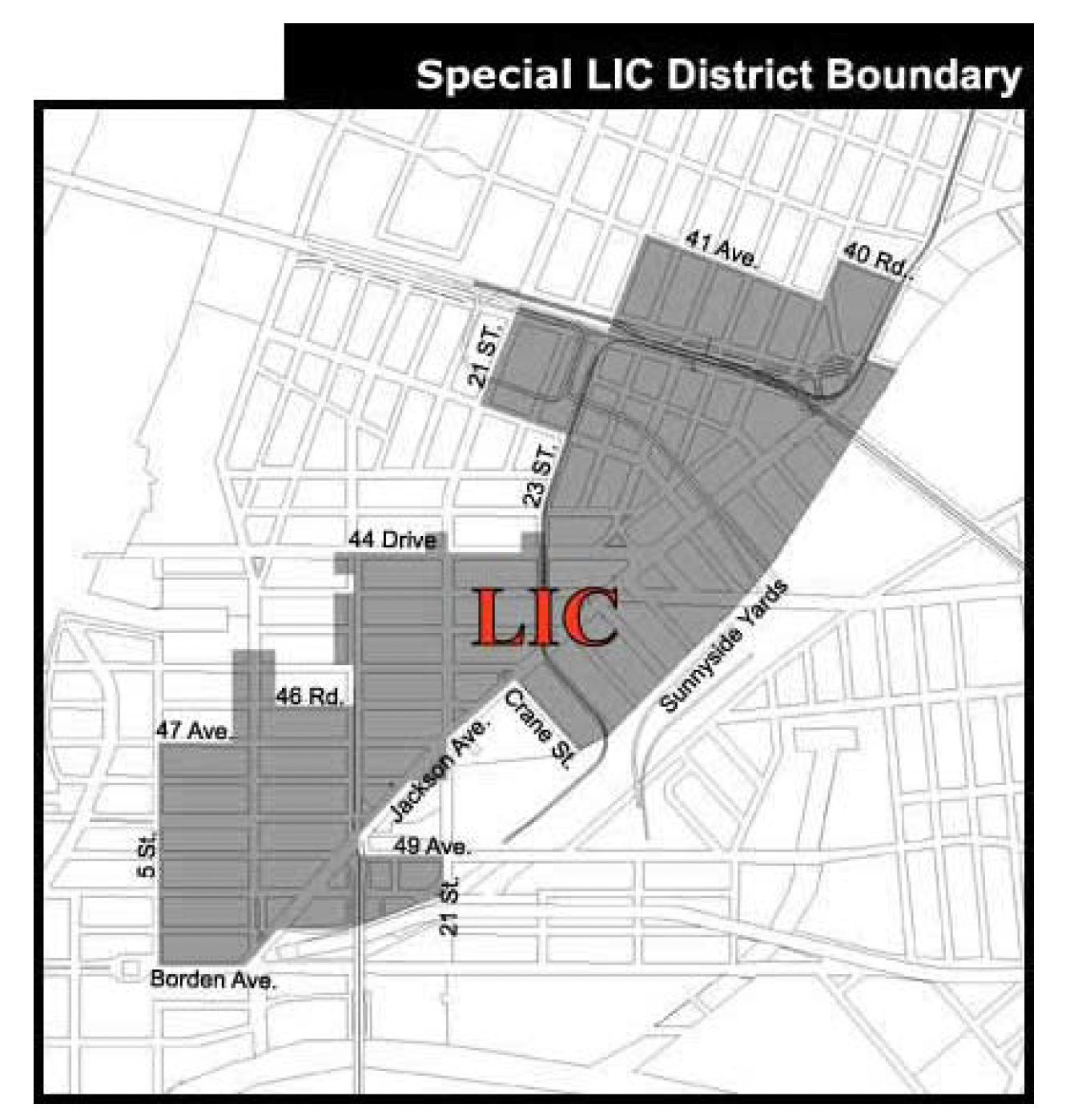

LIC remained largely industrial and unknown to New Yorkers, with a small reputation for prostitution and lack of safety, until 2001. The city rezoned 34 blocks, ending at 41st Ave in the north. It was a watershed moment, and from then on, the LIC that people knew — or more like, didn’t know — was no more.

I met Vanterpool on a rainy day in a high rise by the waterfront, where she used to sit on the ground watching fireworks as a kid. She moved back to LIC last year, after having left 20 years ago. “It was so weird [coming back to LIC]; it’s my home but it’s different,” she said.

LIC’s transformation was very unusual, due to its rapidity. In 2017, LIC became the fastest growing neighborhood in the entire country. Twelve thousand apartments were built between 2010 and 2017, surpassing downtown LA and any Brooklyn neighborhood. LIC’s zip code, 11101, has the third-highest number of apartments constructed in the country, according to data from 2018 to 2022.

It wasn’t just the buildings. The demographics of LIC have also changed rapidly. LIC has had a fivefold increase in Asians since 2010. That’s the highest increase in Asian population compared to any other neighborhood in New York City, according to 2021 data.

When a neighborhood physically changes so rapidly, people are bound to have disagreements over where they think the border is. Those who knew LIC before, when it was just “a ramshackle mix of factories, warehouses and auto-body shops, with homes scattered throughout,” as the New York Times described it 20 years ago, would have different opinions from someone who knows LIC as it is now, a synonym for shiny high rises.

What defines a border?

When I asked Vanterpool where she thinks the border between LIC and Astoria is, she said, “I feel like this is an age-old debate, because LIC is huge and Astoria is huge, and it’s not like this clear cut line. It’s almost like jagged edges.”

Most people’s notion of the border is not a straight line, especially for those who have lived here for decades. For Vanterpool, she struggled with the question and began to list out landmarks that she categorized as either in LIC or Astoria, such as the high schools she attended.

Shannon Ayala, a 36-year-old journalist in Astoria, also believes that the border is not a straight line. If he had to choose, it would be 36th Ave, because that’s where most commercial activities end.

Jonathan Santana-Wang, a 34 year-old court reporter who has lived in Astoria his whole life, said in a heartbeat: “Broadway. I’ve been told it’s Broadway growing up.” He added that the streetlight designs past Broadway are different from those before Broadway.2

In October, the New York Times published a map that showed where its readers thought their neighborhoods were. Indeed, there was no clear cut line between LIC and Astoria, but rather a blurry area spanning blocks between 41st Ave and 36th Ave, where LIC’s color (green) bleeds into Astoria’s (pink).

Besides landmarks, demographics and “vibes” are also key markers people use to determine where the border lies.

“Astoria is very residential, and specific in demographics. You have your Greeks, your Sicilians, highly Middle Eastern [areas], South American [areas], whereas LIC is extremely hipster,” Vanterpool said.

For Ayala, emerging demographics can shift the border. “When new communities emerge, wherever they say the border is becomes where it is.”

Indeed, LIC’s growing Asian community has redefined borders by affecting real estate marketing. This is where Dutch Kills enters the story. Dutch Kills used to be an ambiguous area where industrial LIC blends into residential Astoria.

As Ayala puts it in his blog, “What traditionally separated LIC from Astoria was not a street, but the clustering of residential pockets with much industrial area in between.” The clustering he referred to was Dutch Kills.

Nowadays, however, apartments in Dutch Kills are often marketed as being in LIC. Jiali Hua, a Chinese real estate broker in LIC since 2016, said, “Because LIC is expensive, everyone likes to list [apartments] as LIC.”

However, Hua’s clients, the majority of them Asian, do not feel comfortable in Dutch Kills, she said. This is rooted in a certain perspective on “development”.

“Personally I think beyond Queens Plaza North, beyond the bridge, it’s already not the booming LIC we know,” she said. “I feel like Queens Plaza North and South have a developmental gap of more than 5 years. And if you walk further north, it’s even worse.”

Hua’s perspective that LIC ends at the Queensboro Bridge is likely shared among her Asian clientele. Queensboro Bridge is where the high rises end. It’s the only LIC they know. New York Magazine’s 2017 article titled “Life in LIC, the country’s fastest-growing neighborhood” reverberated the notion that LIC equals luxury high-rises. The entire article discussed high-rise buildings and nothing else.

For Santana-Wang, the question of the border has turned into a battle of “postal zip coding versus real estate agents versus cultural communities.” When I asked whether he still believes that the border is Broadway these days, he resolutely answered “no.”

“Why?” I asked. He thought for a very long time but couldn’t answer.

“I don’t know,” he said.

How the perceived border shifted over time

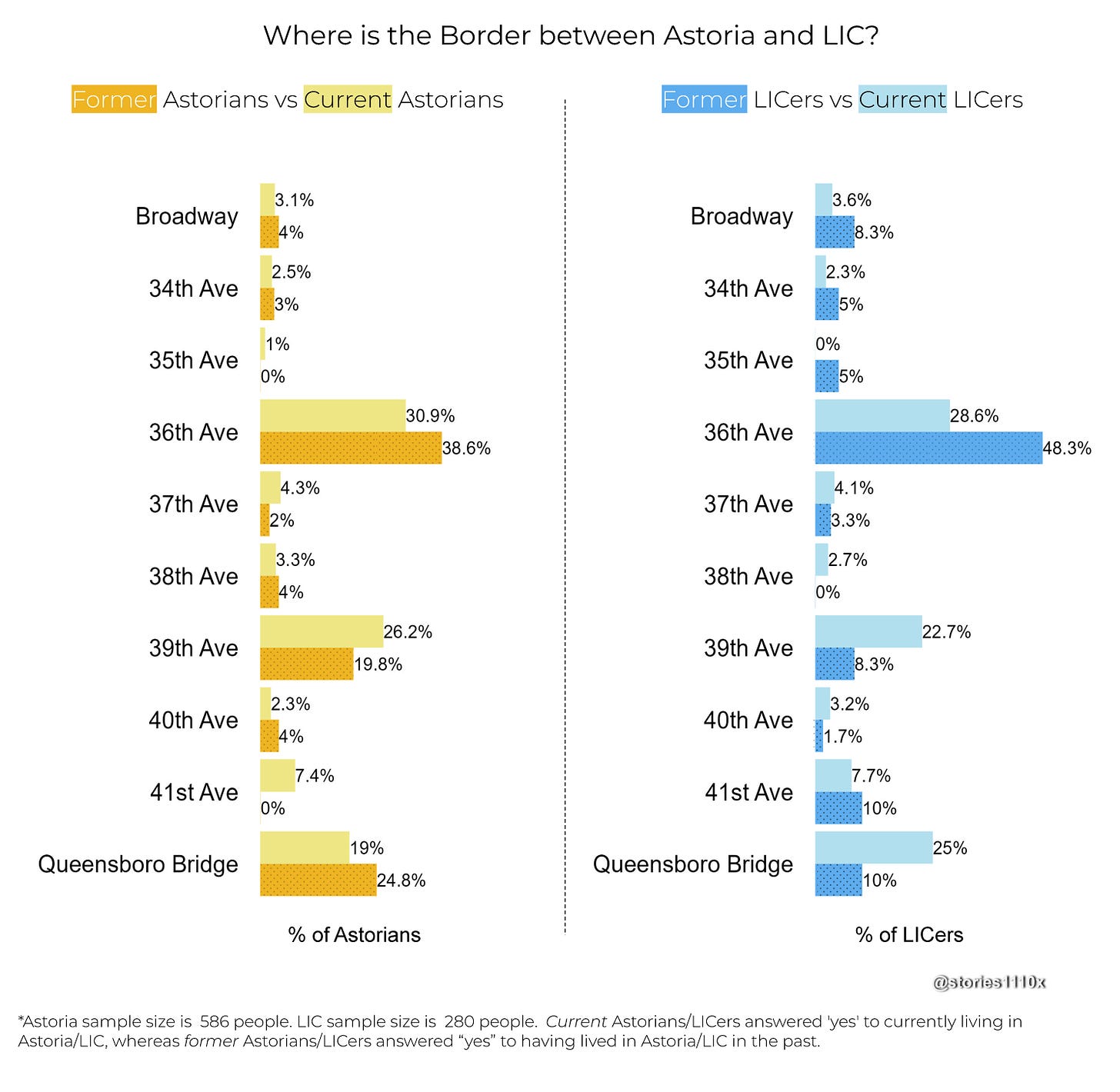

The border between LIC and Astoria has shifted south over the years in people’s minds. Former LIC residents are more likely to think that the border is on 36th Ave. In fact, nearly 50 percent of former LICers believe that the border is there. In contrast, only 29 percent of current LIC residents believe the border is on 36th Ave.

Current LICers, compared to past residents, are more likely to believe that the border is further south, on 39th Ave or at the Queensboro Bridge.

The result is statistically significant at the 99% confidence level, an academic way of saying that former LICers and current LICers are very likely (in fact, 99 percent likely) to be actually different in their answers, rather than just different by chance.

The difference between current and former LICers makes sense. Current LICers see high rises stop at the Queensboro Bridge and are more likely to believe that’s the cut-off. Former LICers, who know LIC for its industrial past, may believe that LIC extends northward, encompassing Dutch Kills.

A similar pattern is observed for former and current Astorians. Former Astoria residents are more likely to believe that the border is on 36th Ave, or just more towards the north, compared to former Astorians.

There is more consensus among Astorians than among LICers,3 likely because LIC has experienced more demographic and migratory changes in the last two decades than Astoria. In Astoria, where there is a lot more home ownership compared to LIC, residents are more likely to have been there longer.

In the coming years, Dutch Kills is likely to become a point of contention as gentrification and LIC’s rising real estate value spread north. Hua predicted that Queens Plaza North, the area north of the Queensboro Bridge, will see the most change in the next five years.

In 2016, Mayor Bill de Blasio proposed another round of rezoning in LIC, this time targeting Dutch Kills. The plan generated a lot of controversy and fears of rising rent among residents. When and if luxury high rises begin to replace Dutch Kills’ current low, residential cityscape, it is going to be a very different gentrification story from LIC.

LIC was mostly industrial prior to the 2001 rezoning, and thus its current developmental boom did not massively displace an existing community. As LIC’s development spreads north, bleeding into Astoria, however, there is likely going to be a difficult clash between new and old communities. By then, the border is undoubtedly going to change again.

At the end of my conversation with Vanterpool, I asked her what’s something that has remained the same in LIC all these years.

“My gosh,” she said. She thought for a long time, gazing out at the East River, before finally saying, “The diversity. Even though the demographics of people has changed, it [has] always been a place for generations of cultures and immigrants… I knew that this area [has] helped develop me.”

Special thanks to Yennie Jun and Aastha Uprety’s contribution in survey design and dissemination.

We were not able to independently verify the streetlight design differences.

In the data, responses from Astorians have a smaller standard deviation than LICers. This may also just be a result of Astoria’s sample size being larger than LIC’s (586 vs. 280 responses).